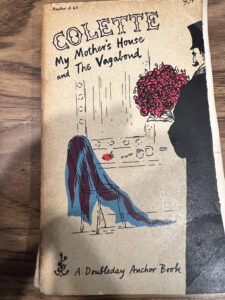

I obtained the book you see pictured here so long ago that, when I read it last week, I had to read in short bursts and take Benydril, because the invisible mold on its pages afflicted my sinuses.

Sidonie Gabrielle Claudine Colette, born in Burgundy, France in 1873, published The Vagabond in France in 1910. It was, translated to English, and republished as the paperback in the picture, by Doubleday, under its imprint anchor books, in 1955. It is published now in English, by Dover Publications.

(My wife, Joanna was working at Doubleday, as assistant to the editor of foreign rights, when it published The Vagabond , which I believe is how we obtained a copy. In the mornings, he was a competent foreign rights editor; in the afternoons, after multi-martini lunches, not so much. During the afternoons, Joanna covered all his bases for him, for a whole lot less pay than he was getting, but that’s a story for another day.)

The best way to classify The Vagabond is as early women’s lib, long before the term was common.

Like Renee, the protagonist, in the novel, Colette made her own living as a travelling music hall performer after divorcing an abusive and unfaithful husband, Henry Gauthier Villars, a prominent literary critic who locked her in a room so she would focus on writing the wildly popular Claudine Series, for which he took the credit and kept the royalties for himself! After her divorce, while performing as a music hall mime, Colette managed to write an average of a novel a year. In 1910, she married again. That marriage ended in 1935 when she married for a third time. This last marriage, to Maurice Goudeket, also a writer, was a happy one. She died in 1954.

The Vagabond closely mirrors Colette’s own life.

Renee has settled into her life as a music hall performer when Maxime, a young, handsome, independently wealthy man arrives uninvited in her dressing room, declaring his admiration and bearing the usual flowers. Still simultaneously grieving for the lost love between herself and her ex husband, and still furious at him, she’s determined to abandon romantic love forever. She dismisses Maxime, addressing him contemptuously as “Big Noodle,” and continues to hold him at bay. But he persists, showing up in her dressing room night after night, until, over time, she falls in love with him.

It is not clear to her whether she wants an enduring, loving marriage, including the pleasures of sex, or is seduced by the comfort and security that comes with marriage to a man so wealthy he has no profession, and who swears he will focus all his energies on making her happy.

The reader has the pleasure of being in her head as she makes her decision, one that covers all the markers of the relations between men and women, and the place of women in society, especially in Renee’s case, the lowly place of unmarried female music hall performers assumed to be licentious, ready to be kept.

It would be a spoiler to tell what Renee decides as she plies her trade in a long absence from Maxine during an extended tour of European cities. Suffice it to say she knows that marriage to Maxine will come with his domination over her, even though that is not what he wants. The very act of caring for her, providing her his home, his wealth, and his respectability is a kind of domination, however inadvertent.

I was compelled by this novel, told in prose, that even in translation is powerfully evocative of the senses. I assume that if The Vagabond were to be made into a film, today’s audience would want the love scenes to be explicit. But it was delicious, to read so-called sex scenes that are not scenic at all. What a pleasure not to know whether the lovers are in a hurry, or take the time to take their clothes off first, whether the woman achieves orgasm or not, and whether the lights are on or off.

What good luck it was to discover this book behind another on my shelves, and to read it for the first time after owning it since 1956!

Leave A Comment