MAKING AN AUDIO BOOK

MAKING AN AUDIO BOOK

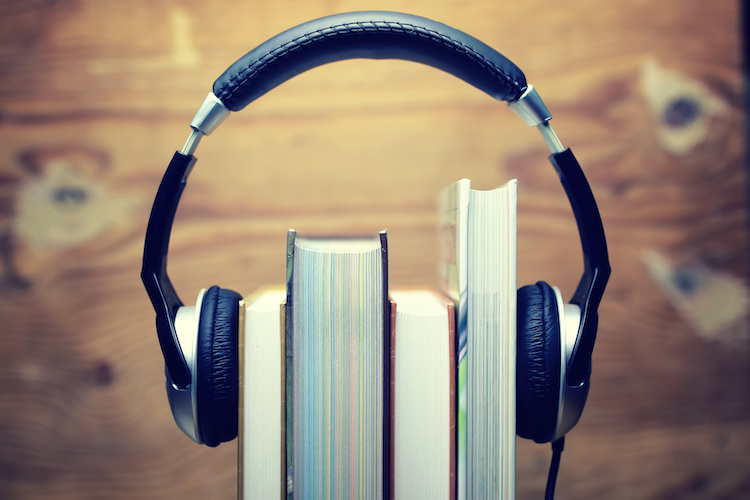

A few months ago, I made an audio version of Ninety-Day Wonder, How The Navy Would Have Been Better Off Without Me, a memoir I had just finished writing about my two-year hitch as astonishingly unqualified officer in the Navy from 1953 to 1955. I am now in the process of deciding whether to publish the print and audio version with a traditional publisher or to self-publish. But that’s not what I want to write about today. Instead, I want to share what the experience of narrating the book in a professional audio studio was like.

I want to share what the experience of narrating the book in a professional audio studio was like.

I had expected it to be very difficult.

I thought audio studios were about the audio only. I assumed I would be on my own about pace, diction, rhythm, when and for how long to pause, or anything else that a neophyte like me would need help on when delivering a story to listeners as opposed to readers. I could not have been more uninformed. I got all the guidance I was capable of absorbing. The process was exciting, satisfying, much less difficult than I had expected, and I am very satisfied with the outcome.

I made the audio at Live Oak Studio, in Berkeley, California.

I should say we made it, James Ward and I as a team. He greeted me as I entered and introduced himself as my director. That word was my first clue that he would do much more than record the sound of my voice; instead, like the director of a film, he would guide me as I read. That is exactly what James did and he did it very well.

The impact of his talking to me when out of sight was to attune me to working entirely auditorily. It was brilliant.

The impact of his talking to me when out of sight was to attune me to working entirely auditorily.

What is interesting to me about his reassurance was that he did not deliver it to me face to face; instead, after he was out of sight, ensconced in another room with all the instruments for recording, and I was seated in a different room where the microphone was placed in the right relationship to me and where I donned earphones through which I would hear his direction and my voice as I read, and where an IPad opened to the manuscript of Ninety Day Wonder was mounted directly in front of me. All I would have to do was scroll down as I read. No sound of rustling pages to disturb the listener. The impact of his talking to me when out of sight was to attune me to working entirely auditorily. It was brilliant.

He told me that when I read too fast, or my voice began to sound tired, or when I slowed down too much, or mispronounced a word, he’d stop me, delete the passage, and suggest how I should re-read it, several times, if necessary, to get it right. He told me that I would get tired so we would take breaks and remind me frequently to drink the water he had provided.

He told me that when I read too fast, or my voice began to sound tired, or when I slowed down too much, or mispronounced a word, he’d stop me

Thus reassured, I started to read.

As James came through on all of his promises, I got more and more relaxed and discovered I was having fun. I remembered how I had loved reading to my children and grandchildren. I heard myself bringing out nuances that might very well not be recognizable on the page. Sarcasm, self-deprecation, amazement that the events I was narrating actually happened, caused me to change my tone of voice – as when we talk to one another, we instinctively change our tone of voice to match our meanings. I felt an intimacy with the potential listeners as if they were right there in the room with me listening to me talk to them. I am convinced that the audio version of Ninety-Day Wonder is better than the print.

Nobody is better suited to tell listeners directly than the confessor.

I am not sure this would be true if it were not a memoir. Audios of novels are most often narrated by professional voice actors who play the parts of the various characters. Memoirs are more intimate. They are confessions. Nobody is better suited to tell listeners directly than the confessor. Nevertheless, I am considering making an audio of The Encampment, the latest novel in the Miss Oliver’s School for Girls Saga. After all, I wrote it. Shouldn’t I be the one who reads it out loud?

Audios of novels are most often narrated by professional voice actors who play the parts of the various characters. Memoirs are more intimate.

I am eager to learn about the experience of other writers who have made an audio book or are considering it.

And from readers/listeners about their preferences: reading or listening. If you are so inclined, do so in the comments. I promise to get back to you.