Like in all great narrative, the opening lines reach beyond the particulars of that narrative to identify for us what is universal in the story, in this case paradise lost, Adam, looking back on what disappeared, the instant he lost his naivete. The world changed while I slept, and much to my surprise, no one had consulted me. That’s how it would always be from that day forward. Of course, that’s the way it had been all along. I just didn’t know it until that morning. Surprise upon surprise: some good, some evil, most somewhere in between. And always without my consent.

‘That morning’ was when his father told Carlos Eire, “Batista is gone. He flew out of Havana early this morning. It looks like the rebels have won.”

In 1962 at the age of 11, Eire was one of the 14,000 children airlifted out of Cuba, exiled to physical safety and emotional turmoil, by, and from, his own parents, because Fidel Castro came to power. Eire’s memoir describes his boyhood with lyrical precision that brings every scene to life and is full of nostalgia, not just for the privilege and affluence he took for granted as a part of the upper crust in Batista’s, world, but also, indirectly, for his innocence about Batista, who, in cahoots with the mafia and the CIA, was a cruel, murderous dictator, surely no less and maybe more, evil than Castro. Eire’s father was powerful judge who sent his children to the same private school in Havana that Batista’s children attended. One of the key moments in the memoir comes when Carlos accompanies his father to the courthouse and watches his father act as both judge and jury, dispensing summary ‘justice’ to the less than powerful, then, after only three hours of work, returning to his comfortable home and art collection.

Memoirs are never about what happened; they are about what the narrator remembers about what happened, and how he or she shades that memory toward one version of truth. Carlos Eire reveals which truth he chooses in the final verse of the poem which serves as the preamble to this stunning memoir:

Still, all of us are responsible for our actions.

Not even Fidel is exempt from all this.

Nor Che, nor his chauffeurs, nor his mansion.

Nor the many Cubans who soiled their pants

before they were shot to death.

Nor the fourteen thousand children who flew away from their parents.

Nor the love and desperation that caused them to fly.

In my opinion, any person with the sensibilities that enabled Carlos Eire to write to write so superb a story would eventually become an outcast wherever he ended up living. If Fidel had lost and Batista won, and Carlos’ family remained at the top of society, still wealthy and powerful, he would have eventually learned that Cuba was never the paradise he had thought it was, because it wasn’t a paradise for most. He would have left in his heart but stayed in place, rather than the other way around. To me, that is what makes Waiting for Snow in Havana universal. This is not a story of what happened to happen to Carlos Eire. This is the story of the nature of exile, of the experience of diaspora, wherever it has happened and wherever it will happen again.

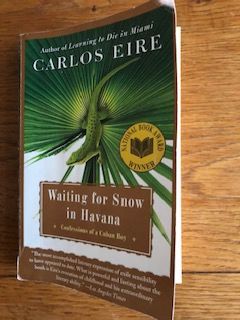

I didn’t read Waiting for Snow in Havana when it came out in 2003. I wasn’t even aware of it. Several months ago, browsing in a bookstore I saw the those words in the title: Snow in Havana? No way could I resist.

This one’s a keeper. I’ll remove a book from my shelves to make room for it, and if I’m lucky enough to still be here in a year or so, I’ll read it again.

Leave A Comment